In the 1980s Seward was demonstrating its Stomacher® technology at a major European laboratory exhibition. At the time the technology was new and in order to show the paddles working the engineers had produced a transparent door. At that show a competitor, keen to take advantage of the recently expired first patent, took a series of covert photographs of this demonstration unit. Later they produced an inferior product with the transparent door as standard. When they realised their mistake the transparent door became an option as opposed to a standard feature.

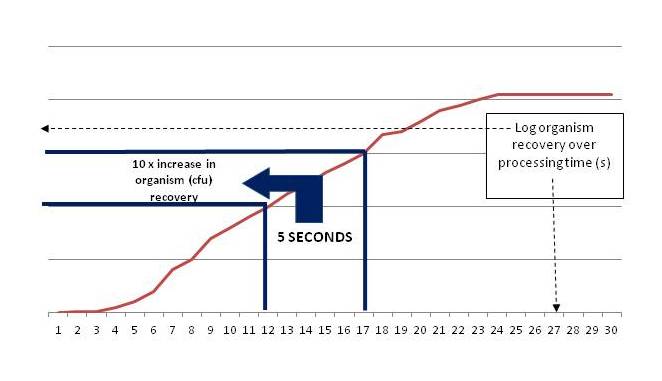

The error they made had already been identified by the engineers at Seward Limited decades earlier. When Seward was tasked with producing its iconic blending solution for the food industry the basic microbiological principles of a quantitative analysis were the basis of the design brief. Key to this was that sample processing should be reproducible. There is a difference in the count of organisms at 10 seconds blending compared to 15 seconds and so on. The data below shows this and it has nothing to do with a qualitative evaluation of what the sample looks like.

Organism recovery is a combination of crushing and washing. Surface attached organisms are as important as those suspended in the food matrix. The progress of this process cannot be visually assessed.

Organism recovery is a combination of crushing and washing. Surface attached organisms are as important as those suspended in the food matrix. The progress of this process cannot be visually assessed.

Reproducibility requires the same processing time and paddle speed every time for the same sample. Microbiology is fraught with volumetric errors and dealing with living organisms introduces many possible additional inconsistencies. Careful control of the factors you can is the mantra of all professional microbiologists. There is nothing to be gained by visual inspection.

This makes the transparent door not only an anachronism but also completely pointless. When Seward was engaged in developing its product major food manufacturers were contacted for their opinions. A major confectionary manufacturer told us that with 2-300 samples a day passing through each of his Stomachers® he had no time to sit and watch the sample go round like he was sitting in the laundrette!

In addition to the scientific and ergonomic issues with the transparent blender door there are also significant engineering issues. We can say with confidence that Seward produced the first transparent doors and investigated a wide range of potential materials. All are too flexible and reduce the effectiveness of the blending process and all rapidly develop surface damage that causes them to lose transparency. On top of this is the fact the transparent panel acts as a drum skin massively amplifying the operational noise level.

In conclusion there are sound scientific and engineering principles behind our choice of door material and as Alice discovered everything through the looking glass may not be all it appears to be.